Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Environmental Education

Section outline

-

-

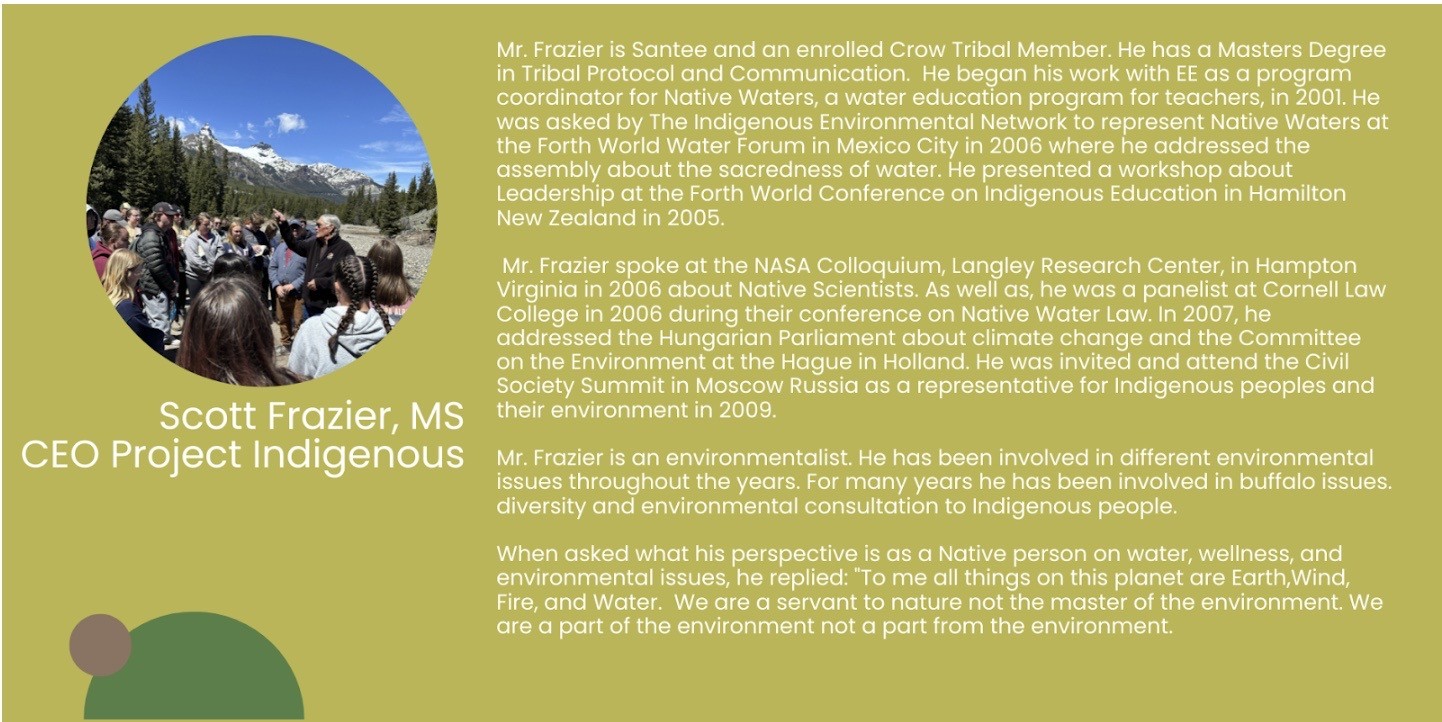

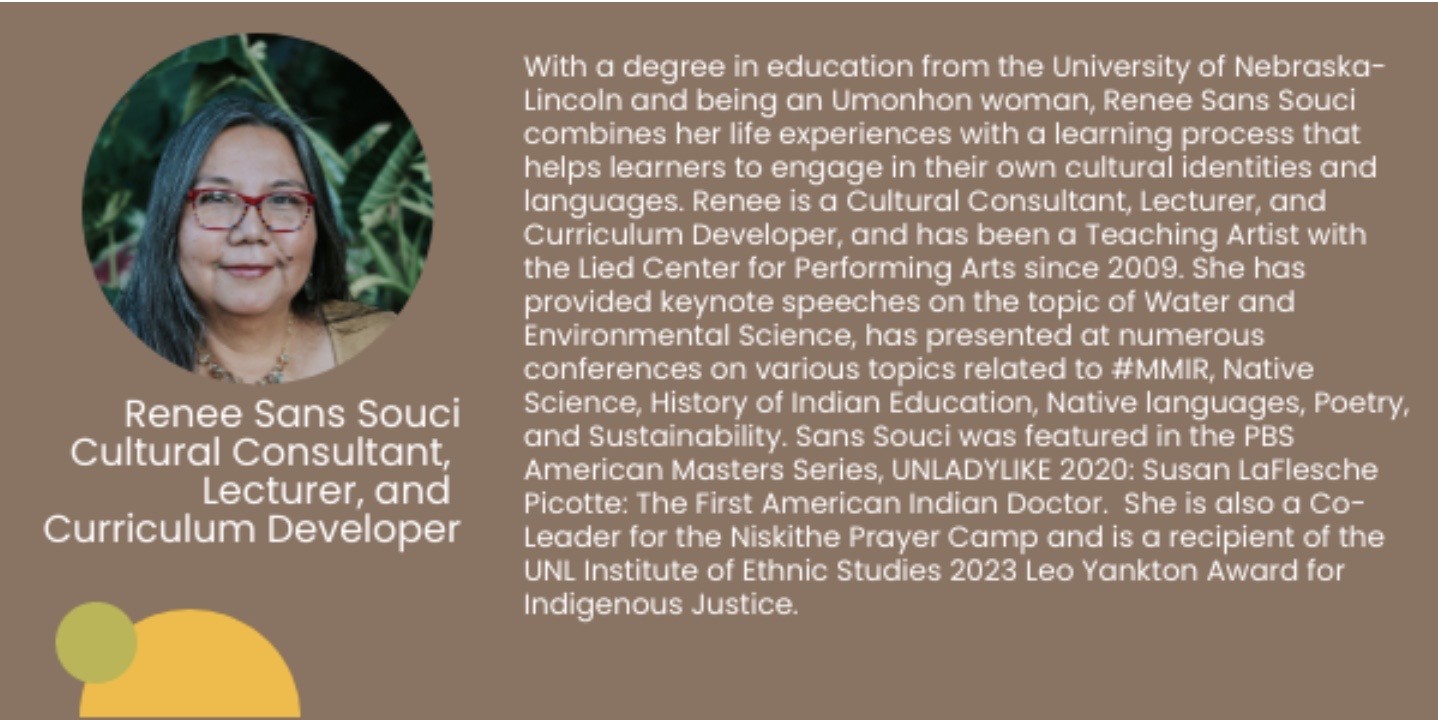

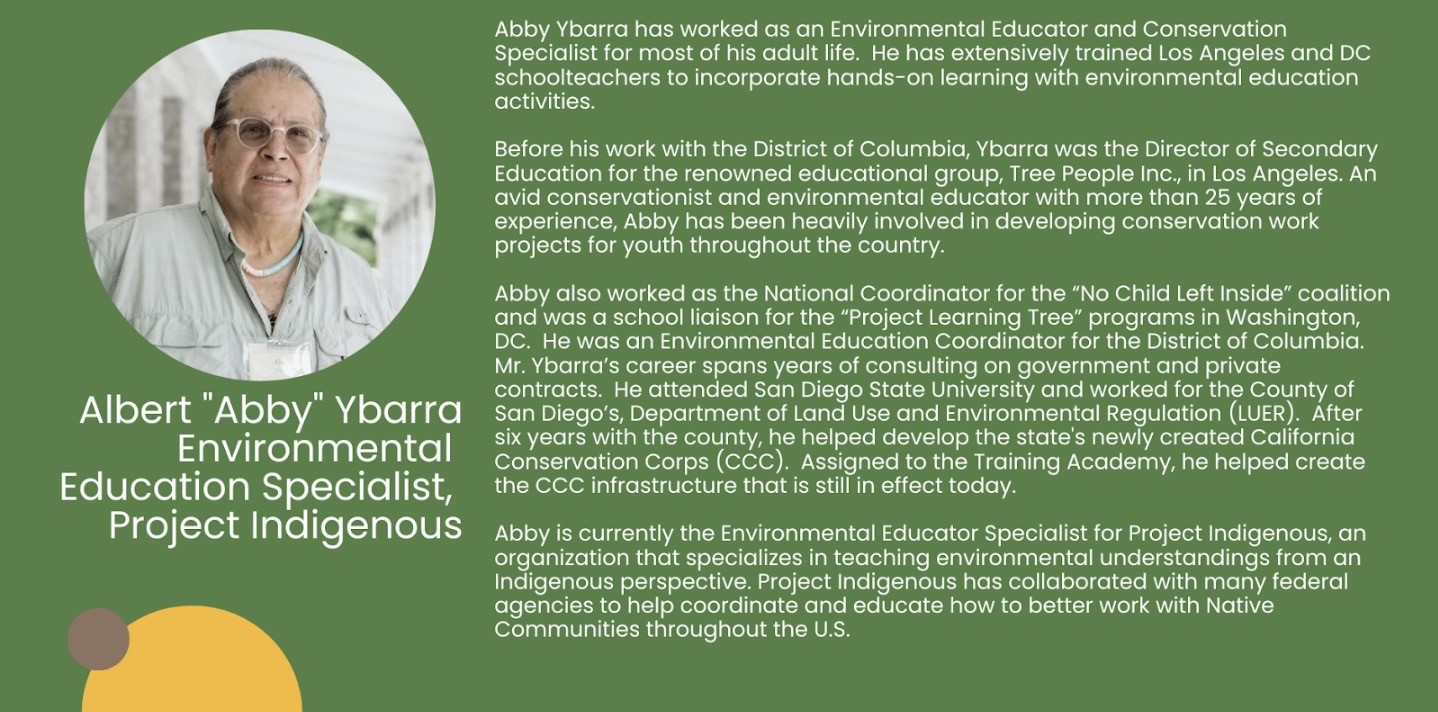

Welcome to Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Environmental Education (EE) eeCourse. This course was developed by Scott Frazier, Santee and an enrolled Crow Tribal Member, Renee Sans Souci, Omaha woman, Abby Ybarra, Yaqui-Tohono O’Odham, the Colorado Alliance for Environmental Education, and the Kansas Association for Conservation and Environmental Education in collaboration with the Missouri Environmental Education Association, the Montana Environmental Education Association, the Nebraska Alliance for Conservation and Environmental Education, the Utah Society for Environmental Education and the Wyoming Alliance for Environmental Education.

This course is designed to provide a strong foundation in Traditional Ecological Knowledge and ways of knowing. It is meant to be an introductory course and spark interest in further learning around how we can more intentionally and respectfully incorporate traditional ways of knowing into our environmental and outdoor learning programming. After exploring background information on TEK, how it compares to Western Science and building relationships and observations as knowledge building, in the final module you will put your new knowledge into a plan to integrate TEK into your teaching.

For additional learning opportunities, please reach out to Project Indigenous and independent consultant Renee Sans Souci.

Objectives and Expectations

By the end of this course, you will be able to:

Describe how you know and share knowledge and compare that with Indigenous knowledge and knowledge sharing.

-

Identify some of the opportunities and challenges in using TEK to address environmental challenges.

-

Develop your personal guidelines for integrating principles of TEK in your teaching which honor, acknowledge and care take TEK and Indigenous people.

-

Compare and Contrast Traditional Ecological Knowledge & Ways of Knowing with Western Science & Ways of Knowing

-

Support your students in developing relationships with the world around them.

-

Teach a lesson or a unit which integrates TEK knowledge and/or practices with your students.

As a student of this course, it is expected that you:

Commit the time required to complete all readings, assignments, and assessments.

-

Complete Modules 1-5 and their associated assignments, as well as submit the final course evaluation. You will have 8 weeks to complete the course.

Prerequisites

Past participation in environmental and outdoor learning is encouraged.

-

Experience working in education is not required but highly encouraged.

Required Materials

- Access to reliable internet and a desktop computer or laptop.

Completing Tasks and Assignments

For each Module, you will record responses to prompts and complete tasks in a Course Journal. At the end of each module, you will submit your Course Journal with the relevant sections completed.

The Course Journal and other documents will be provided in the form of Google Docs. You can either download as a Word document or "Make a Copy" under the File menu to edit it as your own. Assignments can be submitted as Google Docs by using the link-sharing feature. Assignments can also be submitted by attaching Word documents. If you have questions or would prefer another option, please contact Lisa Eadens at lisaeadens@caee.org.

Grading and Optional Course Credit- Assignments must be completed with a score of 2 as indicated on the scoring guide provided.

- If you complete all of the course assignments with a grade of 2 or more you will receive a Certificate of Completion for 15-hours of professional development.

- 1 semester hour of CSM credit can be earned from the Colorado School of Mines for an additional $67. If you are interested in earning CSM credit, you will need to complete the course with a grade of 2 or more on all assignments and pay at te.csmspace.com/register.php?

c=725 at any point during the course term.

Important Dates

This course runs for 8 weeks, from January 27 - March 21, 2025. Although you can complete the course at your own pace, below is a recommended schedule for completing each module:- Module 1 - Complete by February 7

- Module 2 - Complete by February 19

- Module 3 - Complete by February 28

- Module 4 - Complete by March 12

- Module 5 - Complete by March 21

- Course Discussion Option 1 - Friday, March 7th 9-10am (Zoom Link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89005975627)

- Course Discussion Option 2 - Thursday, March 13th 12-1pm (Zoom Link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84004005171)

- Course Discussion Option 3 - Wednesday, March 19th 4-5pm (Zoom Link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/87468949838)

Meet Your Course Moderator

Your course moderator is Lisa Eadens. Lisa is the Program Coordinator for CAEE and has been with CAEE since 2013. She coordinates CAEE's professional development trainings along with the Excellence in EE Award Program and Careers in Natural Resources Initiative. She will review and score your assignments, offer feedback and be available for the optional course meetings to answer questions.

Get to Know the CoursePlease watch this video walk-through from the Kentucky Association for Environmental Education to learn how to navigate course modules, materials, and assignments in Moodle.

This course was supported by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 8 Environmental Education Grants. It has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Agency.

-

Description

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is also sometimes referred to as Traditional Knowledge, Indigenous Knowledge and/or Native Science. This knowledge has been passed down from generation to generation and is a living and constantly evolving way of knowing for Indigenous people today. In this module, you will explore both your own and Indigenous ways of knowing and sharing that knowledge with others, explore the similarities and differences between Western Science and TEK and create a representation of your understanding of what TEK is.

Objectives

After completing this module, you should be able to:- Describe how you know and share knowledge and compare that with Indigenous knowledge and knowledge sharing

- Develop a representation of TEK which represents the key components and/or tenets of TEK.

Benchmark Assessment- Completion of Module 1 Course Journal entries

- View Scoring Guide>>

Estimated Time for Completion

3 HoursBefore You Begin:

Please allow us to introduce you to the course authors. We are pleased to be able to share their Indigenous Knowledge and strong desire for students to engage in developing a deeper connection, understanding, and relationship with the world around them.

Getting to Know the Course and Authors

-

Knowing and Sharing Knowledge--What Is Your Experience?

Knowledge, a cornerstone of human development and progress, encompasses the insights, information, and skills acquired from others, through experience, education, and introspection. It serves as a guiding force, enabling individuals and societies to understand, navigate, and transform the world around them. To begin our exploration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, Indigenous Knowledge, or Native Science, you will first ground yourself in exploring your own knowledge acquisition. What are the ways you come to know something? And how do you share that knowledge with others? How do you use that knowledge in your daily life?

FIRST - Access the Traditional Ecological Knowledge and EE Course Journal. You will need to either Make a Copy of this file and edit it as your own Google Doc or download it as a Microsoft Word document. Click File, Make a Copy or Download. You will record responses to prompts and complete tasks in your own version of the Course Journal throughout this course. At the end of each module, you will submit your Course Journal with the relevant sections completed.

TASK 1: In your Course Journal, reflect on the following:

-

We all gain knowledge through the formal school/education process, but our knowledge expands far beyond what we’ve learned in classrooms. If possible, go outside to a place where you can reflect about something that you’ve come to know in relation to the natural world. Maybe it has to do with plants or animals, maybe rocks or water. Or perhaps with seasonal changes or weather. Zero in on something that you have come to know and tell a story about that knowledge.

-

How did you come to know this? Was it from a caregiver or relative? Was it through observation? What events and/or activities led to you coming to know this?

-

How do you use this knowledge in your daily life?

-

How, if applicable, have you shared this knowledge with others?

-

-

What is Traditional Ecological Knowledge?

Traditional Ecological Knowledge or TEK is a specific way of acquiring and sharing knowledge through observation over time, innovations, practices and beliefs. Transmission of that knowledge occurs through oral and written traditions, song, ceremonies, and representations in clothing, beading patterns, carvings and more. TEK is also referred to as Native Science, Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge and is deeply rooted in a connection to place and the interdependence and relationships between all things in both a physical and spiritual sense. This knowledge is often considered sacred.

This knowledge is crucial for sustainability. However, the process of colonization has profoundly disrupted TEK in numerous ways.

1. Land Dispossession and Relocation: Colonization often involved the forceful displacement of indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands. This separation from their traditional territories disrupted their intimate relationships with the environment, which are essential for the transmission and application of TEK. For example, the relocation of Native American tribes to reservations in the United States severed their ties to lands that were integral to their cultural and ecological practices.

2. Cultural Suppression: Colonial policies frequently aimed to suppress indigenous cultures and languages, which are the primary vehicles for transmitting TEK. Missionary schools, for example, prohibited Indigenous languages and cultural practices, undermining the oral traditions through which TEK is shared and taught. The residential school system in Canada exemplifies this, where Indigenous children were forbidden from speaking their native languages or practicing their traditions, leading to a loss of Ecological Knowledge passed down through generations.

3. Environmental Degradation: Colonial exploitation of natural resources led to significant environmental changes that disrupted Traditional Ecological systems. Deforestation, mining, agriculture, and urbanization altered the landscapes and ecosystems that Indigenous peoples relied upon, making it difficult to maintain traditional practices and knowledge systems. For instance, the extensive logging and mining activities in many parts of Africa and South America have destroyed habitats and biodiversity critical to Indigenous ways of life. There are multiple examples around the world.

4. Legal and Political Marginalization: Colonial and post-colonial legal systems often marginalized Indigenous peoples and denied them rights to manage their lands and resources. This exclusion from decision-making processes about land use and resource management meant that TEK was disregarded in favor of Western scientific approaches. The imposition of Western property laws and the failure to recognize Indigenous rights continue to pose significant challenges for the practice and preservation of TEK.

5. Economic Pressures: The introduction of a market economy and the subsequent economic pressures forced many Indigenous peoples to abandon traditional practices in favor of more commercially viable activities. This shift often led to the neglect of TEK, as younger generations were encouraged to pursue formal education and employment opportunities rather than traditional livelihoods.

1. Wolfe, P. (2006). Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native. *Journal of Genocide Research*, 8(4), 387-409.

2. Alfred, T. (2009). *Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto*. Oxford University Press.

3. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). *Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future*.

4. Battiste, M. (2000). *Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision*. UBC Press.

5. Global Witness. (2018). *Defending Tomorrow: The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders*.

6. Macdonald, F. (2002). Colonizing Our Bodies. *International Journal of Indigenous Health*, 1(1), 23-32.

7. Anaya, J. (2004). *Indigenous Peoples in International Law*. Oxford University Press.

8. Simpson, L. B. (2004). Anticolonial Strategies for the Recovery and Maintenance of Indigenous Knowledge. *The American Indian Quarterly*, 28(3/4), 373-384.

9. Coulthard, G. S. (2014). *Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition*. University of Minnesota Press.

There is an increasing recognition of the importance of TEK and a recognition of the value and relevance of Indigenous and local knowledge systems in contemporary environmental management and sustainability practices. This course seeks to provide educators with a deeper knowledge of TEK both historically and in current practices, as well as expand skills in using TEK practices as a way to connect students to place and develop the skills and mindset to use TEK practices as a way of knowing and sustaining the world around us.

To better understand TEK, first explore more on what TEK is.

TASK 2: Read this brief overview of Traditional Ecological Knowledge from the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) Guidelines for Excellence

TASK 3: Read this overview of Traditional Ecological Knowledge from the Oregon State College of Forestry.

Next explore TEK as compared to Western Science, which is most often taught in schools and centers around scientific processes, theories and laws as represented in science standards and most textbooks.

TASK 4: Exploring Traditional/Indigenous/Native Science and Western Science. To begin, explore this brief overview of TEK and Western Science from Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer from the Grand Canyon Trust. Next, take a deeper dive into exploring TEK and Western Science with Dr. Kimmerer in this video (optional).

. -

TASK 5: Watch this video from Dr. Gregory Cajete talking about Native Science.

.TASK 6: Watch this video from Scott Frazier exploring Traditional Knowledge.

OPTIONAL ADDITIONAL RESOURCES: Power And Place by Deloria and Wildcat

TASK 7: In your Course Journal, choose your way to represent what you see as the key components/tenets of TEK, it could be a drawing, a diagram, a paragraph, a metaphor, a video, a recording, or another method that feels appropriate to you.

OPTIONAL EXTENSION: Go and visit with a parent, grandparent, aunt, uncle or other elder and ask them how to do something that is traditional in their family. Ask them how they learned this or who taught them. -

Opened: Tuesday, 1 October 2024, 1:00 AM

Submit Module 1 Course Journal:

-

Upload your COURSE JOURNAL with MODULE 1 Assignments completed. You may either upload it as a Word document or share a link to your Course Journal Google Document (Be sure that you set the Sharing Setting to “Anyone with the link” and the role of “Commenter”).

-

-

Description:

In this module, you will explore examples of TEK in both historical and modern day as well as the promise of TEK to tackle some of our toughest environmental challenges. Finally, you will develop a set of guidelines which are based in honoring, acknowledging and caretaking TEK in your teaching.Objectives:

After completing this module, you should be able to:- Research, map and provide examples of TEK in different parts of the world, both historical and modern day.

- Identify some of the opportunities and challenges in using TEK to address environmental challenges.

- Develop your personal guidelines for integrating principles of TEK in your teaching which honor, acknowledge and care take TEK and Indigenous people.

Benchmark Assessment:

- Completion of Module 2 Course Journal entries

- View Scoring Guide

Estimated Time for Completion:

3 HoursModule 2 Tasks

-

What Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Look Like?

As you have noticed, Traditional Ecological Knowledge or Native Science is very much connected to place, so the knowledge is extremely diverse. TEK has connections to understanding season and seasonal changes, food, shelter, and practices which support system health and more. What does TEK look like? In this section you will explore some examples from different parts of the world of TEK both historically and current.

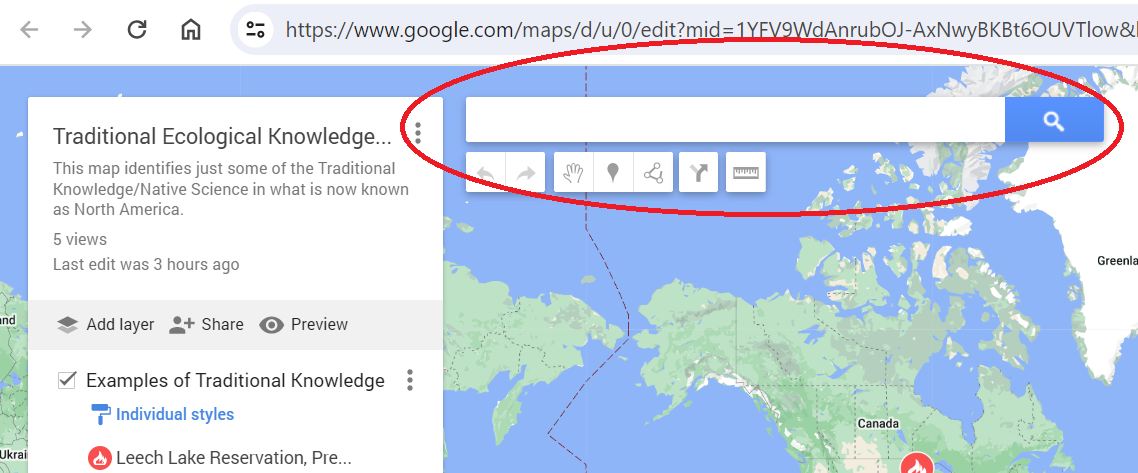

TASK 1: Explore this Google Map to see a few place-based examples of TEK, Indigenous Knowledge or Native Knowledge. As you explore these examples, note what stands out for you in terms of the knowledge, practice and/or current applications. Click on the icons to read more about these examples from the source of the information.

TASK 2: In your Course Journal:

Research other examples of TEK, both historical and current practices and pin your example on this map. The following guidance will help you to expand our map of TEK:

Conduct some research to find an example of TEK that is of interest to you. Be sure to capture the location of the Indigenous People who utilize this knowledge and the source of your information.

Go to this map then type in the location in this search bar and hit enter.

A pin will appear where you have searched. Click on the + Add to Map.

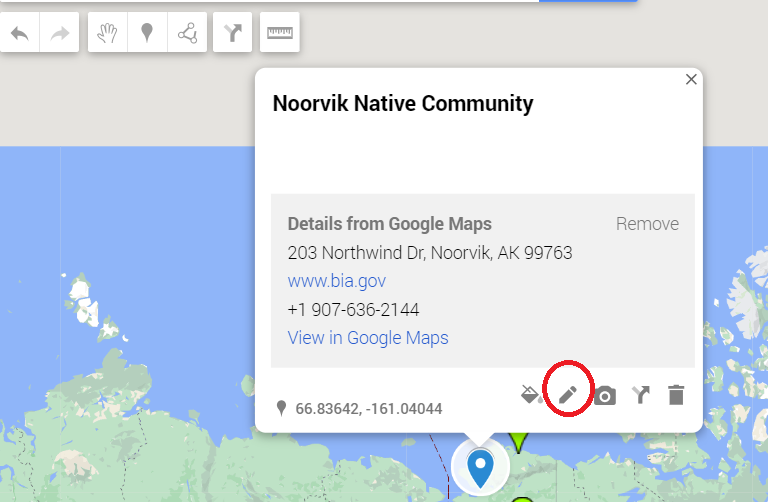

Once you have added your location to the map, click the pencil edit button.

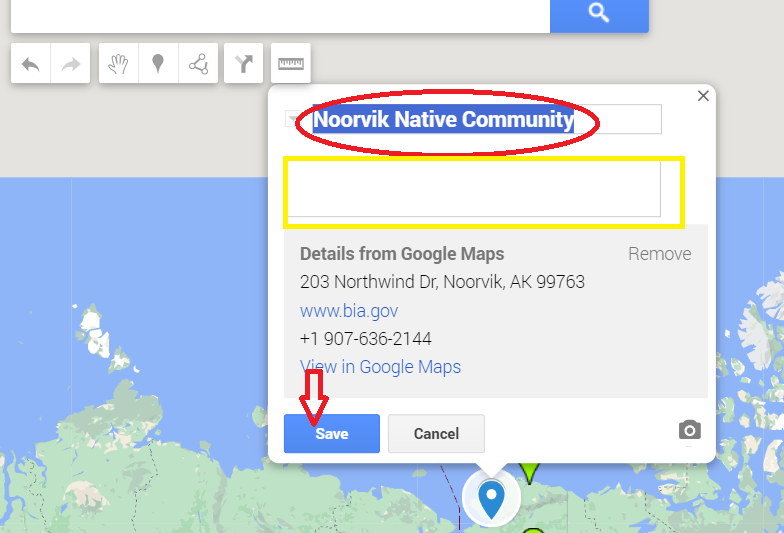

- You can now change the name of the pin to something more descriptive (red circle) and add additional information (brief description and source) in the yellow box, Then hit “Save”.

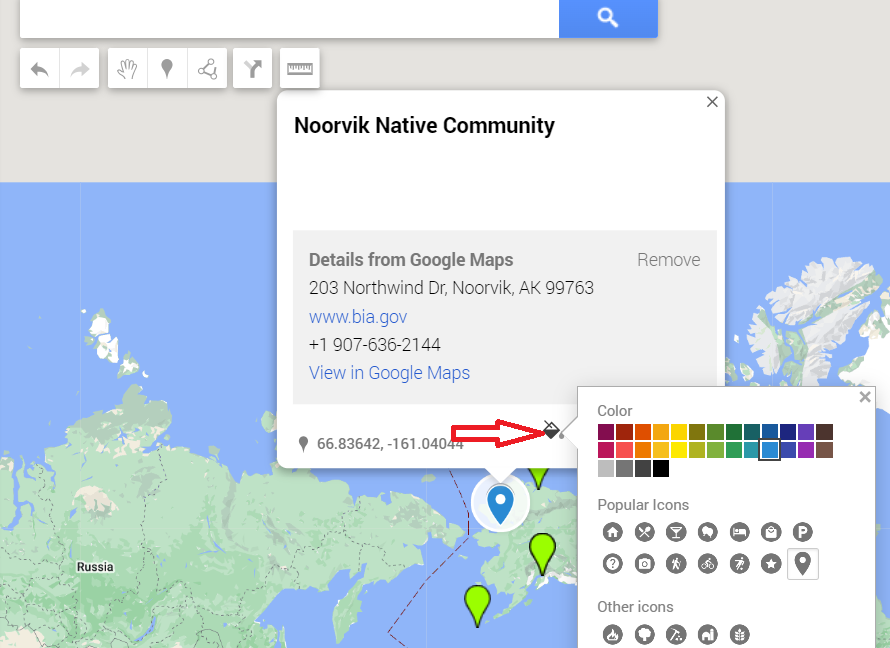

- If you like, you can change the look of the pin by selecting the fill icon. You can then change the color of the pin and/or add a special icon.

TASK 3: In your Course Journal, please provide reflections on the following:

What did you notice as you reviewed the pins on the map?

Why did you choose what you added to the map?

How might you use this information in your teaching?

-

TEK Today

Traditional Knowledge is historical, adaptive, and in use today among Indigenous people and continues to be a part of traditions and customs (like acorn gathering or three sisters gardens). In addition, there is a broader recognition of the importance of traditional knowledge and science as a vital pathway forward. There is an increased collaboration between Indigenous peoples and Western Science tackling some of our most challenging environmental problems. This comes with some opportunities and some challenges. In this section, you will explore some examples of Indigenous people working with Western scientists, some learnings along the way, and applying those learnings to your teaching.

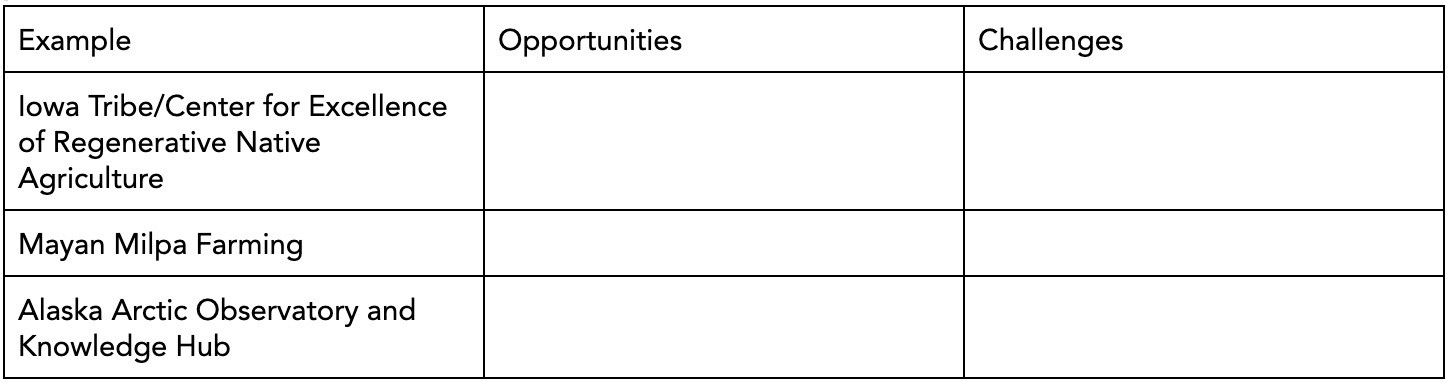

TASK 4: Explore these examples of TEK practices for sustainability which are happening in partnership with non-native partners. As you explore these examples, note in your Course Journal both the opportunities and the challenges/potential challenges that might come from these collaborations:

The Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska received federal funding through the USDA’s Partnerships for Climate Smart Commodities and has established a Center of Excellence for Regenerative Native Agriculture to provide education and support for using Native Regenerative Agriculture practices to both native and non-native farmers.

Explore this example from the Indigenous Mayan people whose use of Milpa farming has received global recognition. Collaborations between the Milpa farmers and local universities, NGOs, and governments are seeking to support and expand their efforts as a sustainable method for food production which also has significant positive impacts on forest conservation in the Yucatan and associated positive climate impacts.

Explore this story map from the Alaska Arctic Observatory and Knowledge Hub, a partnership between the University of Alaska and local observers from Indigenous Knowledge holders across northern Alaska coastal communities.

TASK 5: In your Course Journal, provide your reflections on both opportunities and challenges for each of the examples provided.

-

TASK 6: As the recognition of the importance of TEK in addressing some of our greatest environmental challenges has grown, so too has the outreach to Indigenous people for accessing this knowledge. This has led to some significant challenges. The Indigenous people of Australia discuss some of these challenges in this video. As a result, Indigenous communities came together to develop the Our Knowledge, Our Way Guide to inform best practices in working with Indigenous people. Review the video and the guide as you think about how this could inform your teaching. Make notes in your Course Journal of your key learnings and ideas about how to connect those learnings to your teaching.

TASK 7: Review the article, “5 Things to Know About Indigenous Knowledge When Working With Indigenous Children, Youth, and Families” written by Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon as a summation of TEK, and as you read, reflect on how this might apply to your teaching.

TASK 8: In your Course Journal, develop your guiding principles for teaching TEK. Potential topics to include:

What informs your guiding principles

Important acknowledgements

Key strategies for integrating TEK into your teaching

Opportunities and challenges for integrating TEK into your teaching.

-

Opened: Monday, 30 December 2024, 2:00 AM

Submit Module 2 Course Journal:

Upload your COURSE JOURNAL with MODULE 2 Assignments completed. You may either upload it as a Word document or share a link to your Course Journal Google Document (Be sure that you set the Sharing Setting to “Anyone with the link” and the role of “Commenter”).

-

Description:

In this Module you will compare Traditional Ecological Knowledge and western science to gain an understanding of the differences and similarities and how they shape the way in which we see, understand, learn about, and interact with others and the world around us. As reminded by John Turdell, all human beings are descendants of tribal people and thus, Traditional Knowledge is already within you. This exploration of TEK and Western Science will help you to explore the connections and differences in ways of knowing.

Objectives:

After completing this module, you should be able to:

- Define Two Eyed Seeing and Ethical Space and how it applies to TEK

- Compare and Contrast Traditional Ecological Knowledge & Ways of Knowing with Western Science & Ways of Knowing, recognizing that there is a great deal of diversity of how things were studied within Indigenous culture.

Benchmark Assessment- Completion of Module 3 Course Journal entries.

- View Scoring Guide>>

Estimated Time for Completion

3 HoursModule 3 Tasks:

-

TEK Points to Understand Before You Begin

As you learned in Module 1 Traditional Ecological Knowledge was going along steadily for thousands of years until colonization. After colonization, the education process of Traditional Ecological Knowledge was disrupted. There was a loss of land and language, and then a period of readjustment. Indigenous people were forced through the assimilation process and part of that process was going through the Western education style system of learning. Many Indigenous people are back to their traditional ecological knowledge, and ways of knowing again. Indigenous peoples’ Traditional Ecological Knowledge was not lost and is coming back.

TASK 1: Think about how you have been taught to see and understand the world around you throughout your life. Particularly think about how you were taught these things within the education systems that you have been a part of throughout your life. Read the sections titled “The Why of Indian Education,” “Medicine Wheel Philosophy,” and “Classroom Considerations” on pages 14-15 of the “Interdisciplinary Manual for American Indian Inclusion” by Martin Reinhardt and Traci Maday”

TASK 2: In your Course Journal, record your general thoughts/reflections on the three sections you read from the “Interdisciplinary Manual for American Indian Inclusion” Consider how your thoughts/views may differ from others with different life experiences, perspectives, and backgrounds than you and include this in your reflection.

-

TASK 3: Indigenous Knowledge has had its roots for thousands of years, there was nothing to interfere with it and then Western knowledge came in. Indigenous people had Western education imposed on them and mastered that form of education.

Many circumnavigated the whole process of Western education and emerged on the other side and are back to their traditional ecological knowledge, and ways of knowing, (Deloria, V., Indian Education in America, 2000). It might be helpful to refer back to Dr. Kimmerer's introduction and her experience with higher education. Many Indigenous people examine how to come back to traditional processes and methodologies that their ancestors had and also explore a curiosity for investigating the value of Western science.

photo credit: Jill Haukos

Read the section titled “An Analogy” and review the corresponding images of a tree and cross-section of a tree on pages 11-14 of the “Interdisciplinary Manual for American Indian Inclusion” by Martin Reinhardt and Traci Maday”

TASK 4: In your Course Journal, record your general thoughts/reflections on the section you read and images you reviewed from the “Interdisciplinary Manual for American Indian Inclusion” and answer the following question:

-

How do you feel learning experiences might be different when considering the analogy of learning Indigenous Knowledge systems?

-

-

TASK 5: Now that you have explored the existence of traditional ecological knowledge prior to the Western education system and the opportunities that are already taking place to value both while recognizing which came first, think about what this might mean for your daily life.

In your Course Journal, answer the following questions about how what you have learned about traditional ecological knowledge and the Western education system might affect your daily life:

How has what you’ve learned altered your perception of the world around you?

How could what you learned affect the ways/processes you use to learn about the world around you?

In what ways could what you learned be incorporated into your daily life?

-

Looking at Frameworks for Two Eyed Seeing and Ethical Space

Two-Eyed Seeing is the Guiding Principle brought into the Integrative Science co-learning journey by Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall in Fall 2004. Etuaptmumk is the Mi'kmaw word for Two-Eyed Seeing. We often explain Etuaptmumk - Two-Eyed Seeing, by saying it refers to learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing ... and learning to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all.

Elder Albert indicates that Etuaptmumk - Two-Eyed Seeing is the gift of multiple perspectives treasured by many Aboriginal peoples. We believe it is the requisite Guiding Principle for the new consciousness needed to enable Integrative Science work, as well as other integrative or transcultural or transdisciplinary or collaborative work. - From the Institute for Integrative Science and Health, Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TwoEyedSeeing/

TASK 6: Watch the following video about Two Eyed Seeing to learn about what two eyed seeing is and why it is important developed by Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall.

TASK 7: In your Course Journal, after watching the video about two-eyed seeing, record why you think using two-eyed seeing would be valuable and beneficial to you and the work that you do.

-

TASK 8: When comparing Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Western knowledge another important component to understand is ethical space. The idea of ethical space is creating a safe space, especially regarding discussions about traditional ecological knowledge and Western knowledge. Creating an ethical space for cultural safety when two ways of thinking/cultures can conflict with each other is essential. Read about what ethical space is and just some of the reasons why it’s important as defined by the 4 Directions of Conservation Consulting Services as presented by Gary Pritchard below:

How do you define ethical space?

• The focus of ethical space is on creating a place for knowledge systems to interact with mutual respect, kindness, generosity and other basic values and principles. All knowledge systems are equal; no single system has more weight or legitimacy than another.

• One system does not need the other to “corroborate” it to achieve internal validity. For example, the written system does not always need archaeological evidence to provide sound “proof” of an Indigenous practice or story

Why ethical space is important:

Indigenous Peoples are understandably hesitant to (re)build or establish relationships of trust with settler governments. The usurpation and dispossession of lands, territories, and waters still resonate in the lived realities of Indigenous Peoples across Canada. In addition, Indigenous systems of knowledge, language, laws, customs, protocols, and practices have never been respected as such.

This quote comes directly from 4 Directions of Conservation Consulting Service in Canada and for this course, it is important to note that it is recognized that this applies to indigenous people across Turtle Island and throughout the world.

From 4 Directions of Conservation Consulting Services, see the following link for the full presentation https://cela.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Indigenous-Place-Making-Ethical-Space.pdf

See the diagram below for an illustration of ethical space:

*Optional: Review the following by the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative facilitated by Gwen Bridge to gain a deeper understanding of ethical space.

TASK 9: In your Course Journal, record where there might be opportunities in your life to incorporate creating an ethical space for cultural safety. -

TASK 10: Explore the intersection of two-eyed seeing and ethical space as outlined by the 4 Directions of Conservation Consulting Services below:

Two-Eyed Seeing and Ethical Space:

Ethical Space cannot be cultivated without Two-Eyed-Seeing, which is the practice of learning to see using two knowledge systems, drawing on both to guide discovery and problem-solving. It is within this Ethical Space that all collaboration, mutual support, and multi-directional knowledge sharing occurs.

John Borrows calls these laws ‘gifts’, of which there are seven: Love, Humility, Courage, Generosity, Respect, Truth, and Wisdom. Wisdom comes last, and love comes first, as the Creator, the Great Spirit, the activation of creation comes from love; love is also the underpinning of the Canadian constitution.

Please note that this information came from a consulting service in Canada.

Those Seven Sacred Gifts were organized into a methodology for western and Indigenous cultures to engage one another, specifically academically.

This methodology was founded on parallel governance, with a ‘western business model’ on one side, and oral traditional governance on the other. The goal is not to blend them, but to allow both disciplines to thrive. Ethical space is everything between those parallels, where bridges can exist. For example, a smudge is equivalent to the gavel and the Seven Sacred Gifts are equivalent to "Robert’s Rules of Order.”

From 4 Directions of Conservation Consulting Services, see the following link for the full presentation https://cela.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Indigenous-Place-Making-Ethical-Space.pdf

TASK 11: In your Course Journal, reflect on the value/importance that the practices of two-eyed seeing and creating ethical space for cultural safety have to you. Additionally, include what changes you would like to see in at least two of the following: your local community, place of work, place of religion, social groups, educational systems, etc. to include these two practices.

-

Compare and Contrast Traditional Ecological Knowledge & Ways of Knowing with Western Science & Ways of Knowing

Using what you have learned about Traditional Ecological Knowledge and practices for two-eyed seeing and ethical space, you will have the opportunity to compare and contrast indigenous ways of knowing and understanding with Western ways and identify differences and similarities.

photo credit: Jill Haukos

TASK 12: As you review the compare and contrast table and other resources below, it is important to remember that the goal is to recognize the strengths of both identify ways in which they are complementary, and honor how they are different. It’s imperative to remember and honor that indigenous ways of knowing existed before Western ways and to understand the importance of ensuring that the West doesn’t overpower the indigenous ways of knowing. Further to this point, it’s also important to make the distinction that Indigenous ways of knowing were never lost and it is not a step in going backward to recognize and honor them but instead that they are being brought forward.

TASK 13: In module one you explored several resources on traditional ecological knowledge and you briefly explored comparing Traditional Ecological Knowledge to Western science. In this task, you will do a more in-depth comparison by reviewing the following additional resources on comparing and contrasting traditional ecological knowledge and ways of knowing and Western science and ways of knowing:

-

Example compare and contrast table

-

Qualities associated with traditional (Indigenous) knowledge systems and Western Science (Review the diagram on pg. 9/16)

The resources above include not only examples of how each way of knowing relates to ecology and science but also examples of how each way of knowing relates to several general aspects of life for both indigenous and Western views. This helps give context and background to the ecological and scientific knowledge/ways of knowing for both the indigenous and Western views.

TASK 14: In your Course Journal, in a format that works best for you (paragraph, diagram, table, etc.), your reflections on the following:

-

Overall strengths of both Traditional Ecological Knowledge/indigenous ways of knowing and Western science/ways of knowing.

-

Ways in which you found them to be complementary to each other.

-

How do you think utilizing the strengths of each and the complimentary crossover of the two is beneficial?

-

Where do you see opportunities for utilizing the strengths of each way of knowing and/or the complimentary crossover of the two in your personal and/or professional life?

-

-

Opened: Tuesday, 1 October 2024, 1:00 AM

Submit Module 3 Course Journal:

- Upload your COURSE JOURNAL with MODULE 3 Tasks completed. You may either upload it as a Word document or share a link to your Course Journal Google Document (Be sure that you set the Sharing Setting to “Anyone with the link” and the role of “Commenter”)

-

Description

In this module, you will deepen your own relationship with the world around you and explore what it means to be a good relative to the environment. Everyone was once connected to the earth, but for most, disconnection has occurred. Native peoples are redeveloping their connections and this module provides a process for relearning your connection with your students.

Objectives

After completing this module, you should be able to:- Support your students in developing relationships with the world around them

- Explore with your students what it means to be a good relative to the world around them

- Describe and develop observational strategies that utilize approaches outside of Western Science

Benchmark Assessment- Completion of Module 4 Course Journal entries

- View Scoring Guide>>

Estimated Time for Completion

3 HoursModule 4 Tasks:

-

Understanding Your Relationship with the Environment

TASK 1: In your Course Journal, write one paragraph describing the following:

-

Describe the environment you live, work, and play in.

-

How would you describe your relationship with the environment?

TASK 2: Watch the following videos of Scott Frazier, Santee, and an enrolled Crow Tribal Member, Abby Ybarra, Yaqui-Tohono O’Odham, Renee Sans Souci, Omaha, as they describe their relationship to the environment. Record in your Course Journal any similarities or differences that you noticed in how you described your relationship to the environment.

-

-

Building Knowledge through Observation

Making observations in nature brings us into a relationship with whatever it is that we are observing. During a visit with the Grand Canyon Trust in 2016, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, scientist, professor, enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, and bestselling author of "Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants," explained that Traditional Ecological Knowledge isn't just the result of observing the natural world. She said, "To me, the power and the promise of traditional knowledge is that traditional knowledge, instead of excluding emotion and spirit, invites it in," (Grand Canyon Trust, 2023). During the next set of tasks, you will spend time observing and deepening your relationship with nature.

TASK 3: Find a place where you can watch the sunrise. Spend at least 10 minutes making observations using all your senses. What do you hear, smell, feel, and see? What does it remind you of? What feelings does it invoke? In your course journal, record your observations and feelings. Where did you watch the sunrise? What learnings could you take from your experience? What learnings might you have if you watched the sunrise every day for a year?

TASK 4: In your Course Journal, describe the weather in as much detail as you can. After you have written a description, go outside and spend at least 5 minutes making observations about the weather. What does it feel like? What do you see? Are there smells or sounds that reflect the weather? Re-write your description of the weather without using any Western Science language/measurements (i.e. How can you measure temperature without using degrees?). What is your relationship with the weather?

-

TASK 5: Go on a 15 minute walk nearby your home or workplace. Using all your senses, make observations along your walk. Note the starting point of your walk and the end point. What you hear, smell, feel, and see? What landmarks do you pass? What do the landmarks you pass remind you of? When you return back to your starting point, draw a map depicting your journey without using words. Take a picture of your map and upload it into your Course Journal. What on your map would be most helpful to help someone travel the same route? OPTIONAL: Give your map to a colleague or family member. Were they able to follow the same path? What observations did you record that were the most helpful in sharing the knowledge of where you went?

Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone River, photo credit: Scott Frazier

TASK 6: Find a time and place where you can sit and watch the sunset near your home or workplace. Spend at least 10 minutes making observations. Record in your Course Journal: What observations did you make? How did you know when it was time for the sun to set? Did you use a clock? Has your relationship with the environment around your home and office changed in any way as a result of participating in these activities?

TASK 7: Record in your Course Journal, how might it be beneficial to your students to engage in making observations and building relationships with nearby nature. How might you use these or similar activities with students? -

Gratitude and Reciprocity

TASK 8: Go outside. Find four things that are important to water. Pick one of these things and describe how you selected it and why they are important. What can you learn from them? Explain how you did or could have shown gratitude to the thing you selected for the learning they provided. (Activity created by Scott Frazier, Project Indigenous).

TASK 9: Read the following quotes from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants” that describe a worldview of reciprocity.

“In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.” We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn—we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.”

“Paying attention is a form of reciprocity with the living world, receiving the gifts with open eyes and open heart.”

“Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them.

Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life. Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last. Take only what you need.

Take only that which is given.

Never take more than half. Leave some for others. Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken. Share.

Give thanks for what you have been given.

Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken.

Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

TASK 10: The presence or absence of macroinvertebrates can help indicate the quality of water in streams, ponds, and other waterways. Certain species can only survive in water that is free of pollutants whereas you might find more of other species in polluted water. Imagine you are studying water quality with students and collecting macroinvertebrates from a nearby stream. How might you incorporate gratitude and reciprocity into the learning experience?

-

Summing It Up

TASK 11: Read the lesson, “I notice, I wonder, It reminds me of '' and the accompanying background information from the Beetles Project. In your Course Journal, answer the following questions:

How does this lesson help students develop a relationship with nature?

In what ways does this lesson incorporate traditional ecological knowledge? Are there other opportunities for students to engage in other ways of knowing?

How might you incorporate more opportunities for utilizing Traditional Ecological Knowledge in this lesson?

How might you use a lesson like this with students?

-

Opened: Tuesday, 1 October 2024, 1:00 AM

Submit Module 4 Course Journal:

- Upload your COURSE JOURNAL with MODULE 4 Tasks completed. You may either upload it as a Word document or share a link to your Course Journal Google Document (Be sure that you set the Sharing Setting to “Anyone with the link” and the role of “Commenter”)

-

Description

After exploring background information on TEK, how it compares to Western Science and building relationships and observations as knowledge building, in this Module, you will put this together into a plan to integrate TEK into your teaching.

Objectives

After completing this module, you should be able to:- Teach a lesson or a unit which integrates TEK knowledge and/or practices with your students. .

Benchmark Assessment- Completion of teaching plan for integrating TEK into your teaching and learning.

- View Scoring Guide>>

Estimated Time for Completion

3 HoursModule 5 Tasks:

-

Designing Your Teaching Plan

Review the resources you have been provided as well as any other resources that you have used in your teaching and in thinking about places that TEK and/or TEK practices could be integrated into your teaching. Be sure to refer back to your guide for integrating TEK into your teaching. Use the template in your Module 5 Course Journal guide your design. If there is a different lesson plan format you use or prefer, you may submit that instead but make sure that it includes the same information contained in the template.

TASK 1: Complete an outline of your teaching unit using the template in your Course Journal or an alternate format you prefer. -

Opened: Tuesday, 1 October 2024, 1:00 AM

Submit Module 5 Course Journal:

- Upload your COURSE JOURNAL with MODULE 5 Tasks completed. You may either upload it as a Word document or share a link to your Course Journal Google Document (Be sure that you set the Sharing Setting to “Anyone with the link” and the role of “Commenter”)

-

Opened: Friday, 4 October 2024, 2:00 AM

Your final assignment for this course is to submit a Course Evaluation.

After completing the evaluation and checking the completion box, you will be able to download/print a certificate of completion for your records. The certificate will not appear until all activities and assignments are marked complete and have a passing grade.